They marched all night through snow and frigid temperatures.

At dawn on Nov. 29, 1864, they attacked the Cheyenne and Arapaho camps along a big bend of Sand Creek in far-eastern Colorado Territory.

Twenty-three days later many of those officers and men of the 3rd Colorado Cavalry paraded through Denver as war heroes, having, according to the Rocky Mountain News “donned the regimentals for the purpose of protecting the women of the country by ridding it of red skins.”

When it comes to Colorado landmarks, residents and out-of-staters, alike, often think of the Mile High City, ski resorts, national parks and iconic views. Unless they are also historians or members of indigenous nations, they don’t generally think of the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site as a noteworthy Colorado landmark. I hope to see that change, because in my opinion, no other place within our rectangularly bounded 104,185 square miles more fully represents, embodies and challenges who we are as a people.

Half-a-dozen-and-counting annual “pilgrimages” through our eastern prairie to the site of the massacre have left their mark on me, to the point where I now cherish Sand Creek as the most important and sacred place in my home state. As a fourth-generation Coloradan, a Christian minister and an amateur historian, I believe all our roads lead to Sand Creek in one way or another.

I arrived late to my understanding of Sand Creek as the intersection of our collective past, present and future. I’ve always been interested in history, and in the history of the American West, in particular, but I didn’t learn about Sand Creek until I did some personal research many years after I graduated from college. I went to Denver schools K-12 but never remember a lesson on the massacre. As a kid, I did watch part of the ’70s TV miniseries Centennial, but all I remember of it is when the pioneer lady gets bitten by a rattlesnake and dies.

What I didn’t know until recently was that traces of Sand Creek were all around me. No one I knew seemed to have any idea they were there either. For example:

- I grew up in Southeast Denver and often traveled west on Hampden Avenue, which meant I saw a lot of the unmistakable ice cream-scooped landmark known as “Mount Evans.” This prominent Front Range fourteener is named after John Evans, founder of Northwestern University and Colorado Seminary, later the University of Denver, whose mascot, not incidentally, is the “Pioneers.” Evans was governor of the Colorado Territory in 1864, and although he wasn’t physically present at Sand Creek, he played a central role in instigating the massacre there. The Northern Colorado municipality of Evans is named after him.

- “Evans Avenue” runs east-west not far from Hampden and nearby “Downing Street,” which is named after Jacob Downing, a prominent Denver lawyer and unapologetic participant in the slaughter at Sand Creek. There are no towns named after Downing, but there is still an unincorporated community in Kiowa County known as Chivington, after the minister-turned-U.S. cavalry officer John Milton Chivington, who masterminded and led the massacre at Sand Creek.

- Along with “Mount Evans,” mentioned above, there are two other prominent 14,000-foot mountains of the so-called “Front Range” of the Colorado Rockies. We know them as “Pike’s Peak” and “Long’s Peak,” after U.S. Army explorers Zebulon Pike and Stephen H. Long, who mapped this area in 1806 and 1820, respectively. As a conscious attempt to reject (but not forget) our settler-colonial heritage, I now refer to these landmark peaks by their Hinono’eino’ (Arapaho) names: “Two Guides” for Long’s Peak, “Mountain Where the Mist Is” or “White Mountain” for Mount Evans, and “Long Mountain” for Pike’s Peak.

- We call Colorado the “Centennial State” because it joined the Union in 1876, one hundred years after the signing of the Declaration of Independence. That’s usually as far as we delve into the backstory of our state’s nickname, but it’s time we also acknowledge that a tacit prerequisite for our statehood, like the 37 states that joined the United States before us and the 12 states that joined after us, was the displacement and/or subjugation of the indigenous peoples who made their home here for many generations before white settlement.

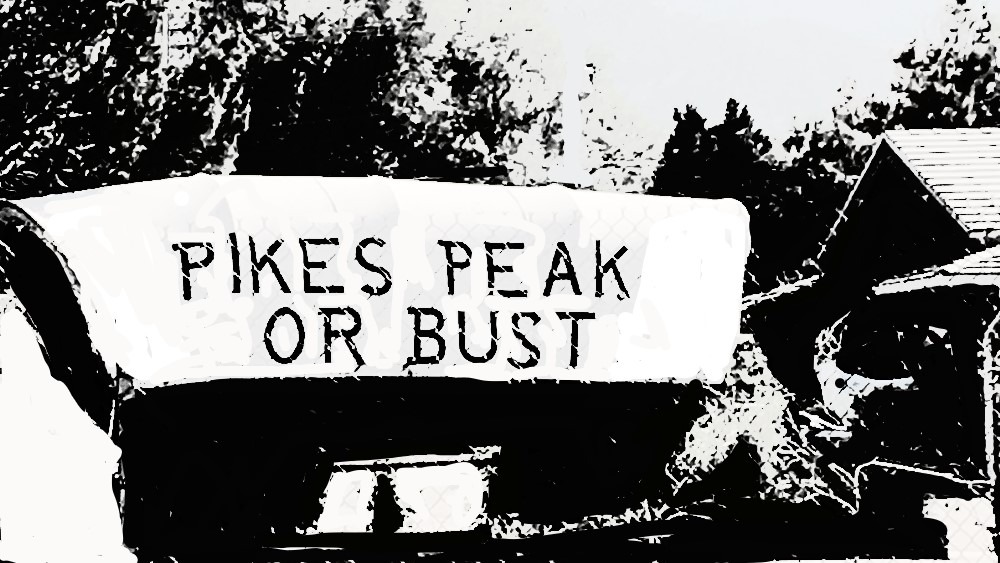

- Prior to Sand Creek, Cheyennes under Mo’ohtavetoo’o (Black Kettle), and other leaders frequented the Front Range, and so did bands of the Ute, Kiowa, Lakota, Comanche, Pawnee and Apache nations. Arapahos camped regularly in the Boulder Valley and near the confluence of the South Platte River and Cherry Creek in what is now Denver. Not incidentally, our capital city is named for James W. Denver, the territorial governor of Kansas during the 1858 Pike’s Peak Gold Rush. “Pike’s Peak” then referred not only to the fourteener we know by that name, but also to the entire region, which is why some of the tens of thousands of prospectors and fortune seekers headed for the western edge of what was then Kansas Territory wrote “Pike’s Peak or Bust” on their covered wagons.

- In 1861, as Southern states were seceding from the Union, the Colorado Territory was born. Just three years later, the 3rd Colorado Cavalry Regiment, along with elements of the 1st Colorado Cavalry, massacred more than 200 Cheyenne and Arapaho people, mostly elders, women and children, precipitating the corporate displacement of both nations from the Front Range of Colorado.

In true American fashion, while the Cheyennes and Arapahos eventually found themselves in Oklahoma, Wyoming and Montana, their names remained attached in various ways to their Colorado homeland. For example:

- In the Denver and Boulder areas we drive main east-west roads known as “Arapahoe.” Also, “Arapahoe County” is the third most populous in the state. In the mountains, we hike in the “Indian Peaks Wilderness” and the “Arapaho National Forest” in sight of the “Arapaho Peaks.” On the way to Sand Creek, there’s a turnoff to tiny Cheyenne Wells, Colo. Earlier I mentioned the Arapaho leader “Nawath,” known more popularly as “Niwot,” or, in English, “Left Hand,” who is the namesake of Boulder County’s Left Hand Creek, Left Hand Canyon, Left Hand Brewing Company, Niwot High School and the “census-designated place” of Niwot.

- Growing up, my family and I often drove past what we knew as “Cherry Creek Reservoir” adjacent to I-225. The Arapaho called the creek, dammed to regulate and prevent flooding, “The Place Where the Chokecherries Grow.” Before white settlement, vast numbers of fat, ripe chokecherries attracted buffalo herds to the area. It’s not so much the practice any more from what I can tell, but in the 1980s and 1990s, mischievous local high schoolers dug and burned the initials of their high schools into the I-225-facing side of the Cherry Creek Dam. Sets of initials included “TJ,” “OHS” and “CC.”

- “TJ” stands for Thomas Jefferson, the high school my four siblings and I attended. Because of my athletic, if not scholastic, loyalty to our school, Thomas Jefferson was for many years my favorite president. I knew him for his red hair, his primary authorship of the Declaration of Independence, and his 1803 acquisition from the French of the Louisiana Territory, which included a portion of what is now Colorado (then home to many indigenous nations), for $15 million or less than 3 cents per acre.

- “OHS” stands for Overland High School, whose mascot is the Trailblazers. Both names refer to the Overland Trail, a 19th-century wagon and stagecoach route connecting Kansas with what is now Colorado and Wyoming.

- “CC” stands for Cherry Creek High School after the above waterway, but at least in those days, incorporating and eliciting images of ripe maraschino-looking cherries, not chokecherries. Again, not incidentally, early prospectors discovered gold along the headwaters of Cherry Creek, near what is now Elizabeth, Colo., a town named for a family member of John Evans.

Speaking of the crucial role played by gold and gold fever in the formation of my state, we have the town of Golden, Colo., originally called “Golden City” after the aptly named Georgia prospector Thomas Golden, who likely left Colorado to enlist in the Confederate Army in 1861. Other prospector-settlers named their camp at the confluence of Cherry Creek and the South Platte, “Auraria,” after a gold prospecting camp by the same name in Georgia. Today, Auraria forms part of downtown Denver.

The names of once and current Colorado mining towns, in particular, trace our familiar path of prioritizing private property — through patents, deeds and claims — to extract or otherwise appropriate natural resources for financial gain: we have “ghost towns” such as Eureka, Goldfield, Gold Park and Oro City, and still viable small communities such as Gold Hill, Silverton, Silver Plume and Eldora, shortened from El Dorado, as in the legend of a golden civilization ripe for the taking. Thanks to the 1862 Homestead Act and other government incentives, farming communities like my adopted hometown of Broomfield, Colo., sprouted up throughout Colorado to feed hungry mining camps. Some towns, like nearby Louisville combined mining (for coal) and farming.

In a related vein, the U.S. government built and maintained military outposts to train troops, project power and protect white prospectors and other settlers from Indian depredations. Chivington marched his force overnight to Sand Creek from one of those outposts, Fort Lyon, originally named Fort Wise after the then-governor of Virginia, but renamed after the first Union general killed in battle with Confederates (at Wilson’s Creek, Mo., in 1861). Other forts in operation in 1864 included Fort Garland in southcentral Colorado; Camp Collins, located in what is now Old Town Ft. Collins, Colo.; and Camp Weld, near what is now downtown Denver, where Gov. Evans and then-Col. Chivington reluctantly held council with Black Kettle and other Cheyenne and Arapaho chiefs in September 1864. Military outposts also coordinated with settler fortifications like Fort Chambers in present-day Boulder and privately owned and operated trading posts like Bent’s Fort on the Santa Fe Trail in southeastern Colorado.

The economic, civic and military paths followed by our settler-immigrant forebearers led inexorably to Sand Creek, having met and overlapped with another crucial element — religion.

Citizens of the United States have long claimed the blessing of Divine Providence with the fervor of a grizzled miner staking his claim to a promising stretch of creekbed. Like Byzantium of old, American-Christian-Exceptionalism amalgamated God’s blessing on the imperial and individual ambitions of the United States and its people and the idea of biblical chosenness. Voilà! Our “one nation, under God” outdueled the Christian-Exceptionalist claims of France, Spain and the United Kingdom, and it did so at the expense of indigenous peoples “from sea to shining sea.” American-Christian-Exceptionalism echoed from the spires of churches, the dome of the U.S. Capitol, and the hearths of its citizens through countless sermons, speeches and letters in the 1800s (and sadly it’s still around today, but that’s a topic for another post).

John Chivington personified this peculiar institution (i.e. American religion), although he vehemently opposed America’s other “peculiar institution” (i.e. slavery). Born in Ohio, he received his ordination in the Methodist Church in 1844 when he was in his early twenties. He served in Illinois, Kansas and Nebraska before moving to Denver in 1860 to lead his denomination’s Rocky Mountain District. An imposing figure, he preached boldly to miners about the evils of alcohol and debauchery. When the Civil War came, he volunteered to help preserve the Union as a fighting officer in the Colorado Cavalry. Along with pre-war legends surrounding his fiery abolitionist sermons, his exploits against a Confederate army of Texans at the Battle of Glorieta Pass in northern New Mexico Territory in 1862 earned him the title of “the Fighting Parson.” In those days, along with explorer Kit Carson, Chivington may have been the most famous person in the Colorado Territory.

Apparently, he had trouble, or more likely, chose to have trouble, distinguishing between “friendly” and “hostile” Indians. Case in point: Chivington and his men attacked Cheyennes and Arapahos who had peacefully followed U.S. military instructions to camp at Sand Creek, while at the same time ignoring a much larger and well known base of “hostiles,” including Cheyennes, Arapahos and Lakotas, farther to the northeast in the Smoky Hills of Kansas.

On the eve of the attack, Chivington reportedly referred to Indian children at Sand Creek as “nits,” the eggs of insects, destined to become “lice.” He clearly was not alone in his desire to teach the Indians a lesson, as most of the 700 cavalrymen he commanded on Nov. 29, 1864, obeyed his early morning order to attack and take no prisoners. Despite several official investigations into the massacre at Sand Creek, Chivington was never charged or prosecuted. He remained a popular figure in Colorado until his death in 1894.

In 2007, the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site opened to the public.

In 2014, Governor John Hickenlooper issued an official apology for the Sand Creek Massacre.

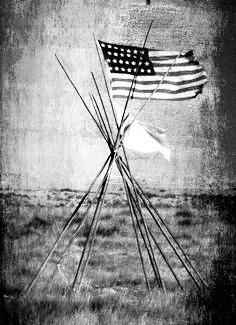

Each November for the last 20 years, Cheyenne and Arapaho descendents of massacre survivors have run in relays from southeastern Colorado to Denver in what is known as the “Sand Creek Spiritual Healing Run.”

A (Short) Bibliography

For a driving tour of Denver sites related to Sand Creek, check out this page in my “Pilgrimage” section.

For a thorough treatment of the dehumanizing attitudes and actions white Americans have directed toward indigenous peoples, read Richard Drinnon’s Facing West.

For an eye-opening account of American history “from below,” read Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz’s An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States.