When I first met my soon-to-be step-father-in-law on his farm outside my then-girlfriend’s small Missouri hometown, the first thing he said to me was, “You’re not from around these parts, are ya? You’re a Yankee.” Having grown up in Denver, Colo., I had never thought of myself as a Yankee before, so I wasn’t quite sure how to respond to his good-natured, half-serious ribbing. Ultimately, I didn’t mind it because where I come from people did the same sort of thing. The only difference is we used green-and-white “Native” bumper stickers with the mountainous outline of the Front Range to identify ourselves as the only real Coloradans.

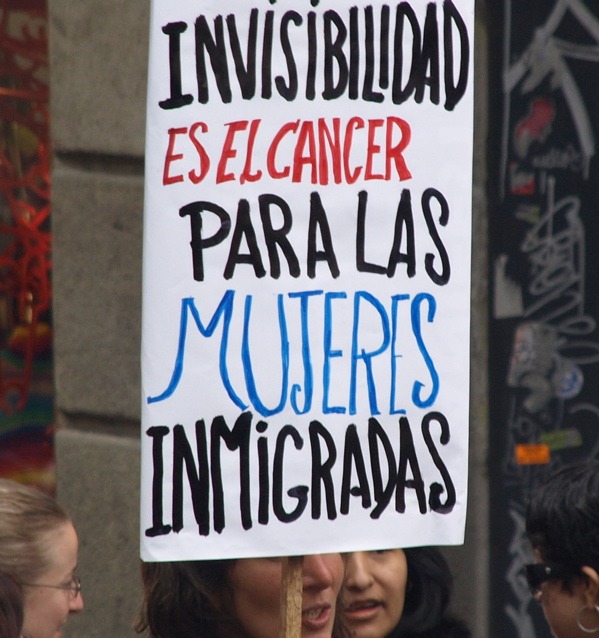

There’s something to be said for hometown or home state pride, especially since the increased mobility of our society has led to the breakdown of family and community ties and all the upheaval those breakdowns entail. We go wrong, though, when we take our “us”-ness too far and choose to focus only on our differences from others instead of on what we have in common. And so we give disparaging names to people who aren’t like us or aren’t from where we’re from — we call them “strangers,” “outsiders,” “foreigners,” “aliens,” “immigrants,” even “illegals.”

I didn’t start questioning our dehumanizing vocabulary of the “other” until I became an “other” myself. For 14 months between 2007-08, my then-family of four and I lived near Barcelona, Spain, where I helped a few friends make short films. Since we originally planned to live there for two to four years we had to navigate the Spanish immigration system to maintain our visa status as temporary residents. That meant paying various fees, closely monitoring our paperwork and dreading day-long waits in long lines that stretched out the door, around the corner and down the street from the “Oficina de Extranjeros” (“Foreigners’ Office”).

Although I had to wait in line and pass security checkpoints like all the immigrants from Latin America, Eastern Europe and Africa, my U.S. passport (and the associated assumption that I could easily pay my fees) partially shielded me from the rapid-fire wrath of the bureaucrats who ran the system. Here’s what they communicated with their attitude, words and body language:

- Can’t understand me when I talk as fast as I possibly can? Too bad.

- Brought the wrong paperwork? Too bad.

- Can’t make yourself understood quickly enough? You are dismissed. Next in line.

- Showed up at the wrong office? Too bad. (There are several connected offices for immigrants in Barcelona.)

- Couldn’t understand the instructions on your visa paperwork? Too bad.

- Didn’t know about the unpublished rules that govern your visa? Too bad.

- Didn’t bring all of the members of your family with you because the person you talked to last time said you didn’t need to? Well, you do in fact have to bring them all with you. Come back next week.

- Didn’t know about the new, additional fee the department had just instituted? Come back when you have the money.

Every time except the last time I showed up at the Oficina de Extranjeros, I left feeling isolated, stressed and unwelcome as an outsider in an unfriendly and hostile system. I say “except the last time,” because my family and I did get our visa paperwork approved in the end. We went to the zoo and watched some dolphins perform to celebrate.

I get that every country, including mine, has immigration and visa procedures (and problems). I get that it’s not practical to expect all countries around the world to completely open their borders. What I’m saying is that it was easy for me to view others with suspicion and indifference as long as I was in the position of power as a native in my own land, but it was not easy at all to be viewed with suspicion and indifference in an unfamiliar place where I didn’t speak the language well.

A very famous teacher once said, “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” What would happen if we allowed that principle to help shape our civic, social and personal views of Us-ness and Them-ness?

Come back next week to consider a few possible answers.