After his second year of law school, Jose Escobar met his first client, Maria*, a single mother with two kids whose biological father had moved to California. Though Maria’s estranged partner had left his family permanently, that didn’t stop him from borrowing a baby that wasn’t his for a trip to apply for social service aid. He was on welfare for four years when the state of California started garnishing Maria’s wages, even though she had been in Denver, Colo., caring for their son and daughter that whole time.

“That’s called fraud,” Jose says, his voice thick with understatement.

Maria was already struggling to make ends meet when California began taking one-third of her wages. She had to quit her job to survive, living off welfare and food stamps and moving into Section 8 government housing while she tried to fight California’s legal action. She couldn’t afford an attorney, so for two years she fought alone, pleading in California court after California court, only to be told each time that she was in the wrong court and had to start her appeal process from scratch.

Eventually, Maria found her way to the Justice And Mercy Legal Aid Clinic (JAMLAC) near downtown Denver, where she met the clinic’s director, Steve Thompson.

Jose’s timeline

|

“So Steve hands me, his intern, the case, and it took some research,” Jose says, recalling Maria’s despair. “The statue of limitation had flown over with this case. They said she owed more than $20,000, because the state was going after the money…paid [to the father] for welfare for the kid he didn’t have. The problem was it was in California, but the state of California wouldn’t talk to her. She’d be on hold for hours with the DA’s office.”

“But because I’m a lawyer, they talked to me in two minutes. They go, ‘Yeah, alright, let’s see what we can do.’ We go back and forth. It takes four or five months, because the state court…machinery doesn’t deal with the case until it goes to court.”

The day of Maria’s court date via teleconference, she was praying when she met with Jose. He remembers, “She said, ‘God told me today’s the day something good is going to happen,’ but I said, ‘Hold your horses. We could get squat. The…judge could kick [the case] out.’

“Then the court clerk from California calls up [and says], ‘We’re all on the line.’ I spoke with an attorney from the DA’s office. He goes, ‘Yeah, this is definitely fraud, so why don’t we just give her all the money back,’ and I said, “Okay.” And it’s done.”

“Of course, [Maria] starts crying and I’m trying not to, but I totally can’t do it. I go in front of a judge, by phone, and the state says, “All the money should go back to her,” somewhere around $8,000, and the judge says, “Okay.” Done deal. I talked to the judge for literally two minutes. The culmination of years of work could all be compressed into a two-minute discussion I had with the [district] attorney and two minutes with the judge, and she got all her money back.”

“If she doesn’t have an attorney, she still owes more than $20,000.”

“Here’s the best part…a month later, I talked to her and she said, ‘I want you to know I got a job [as a] bank teller. I can get off welfare and live like a normal person!’ And she was off and running.”

The perfect storm

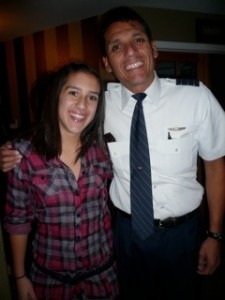

Though Jose didn’t originally envision himself as a “street lawyer,” the hope that he could help people is what propelled him to take the LSAT, apply for and get a competitive social justice scholarship to the University of Denver Sturm College of Law, and earn his law degree in three years, all while working full-time as a pilot and trainer for United Airlines.

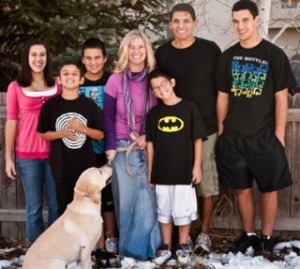

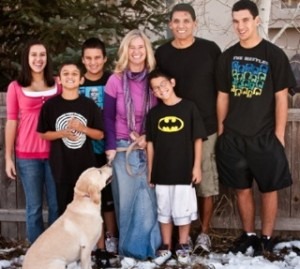

“It was one of those perfect storm kinds of things,” Jose says. “You can say it’s God, it’s a coincidence, whatever you want. I was going to my [20-year Nevada] high school reunion, looking through the yearbook to remember, and they spotlighted me my freshman year, “What are you going to do? What are your dreams?” and I was looking over it with my kids. [In the yearbook] I said, ‘I want to go to UCLA and be a lawyer.’ And so my kids were like, ‘What up, dude? You didn’t do it. What happened?’ And then my mom actually had just recently…said, ‘Hey, you should go to law school.’ I said, ‘I’m too old, I have five kids.’ You start lining up all the obstacles…I certainly can’t pay for it…But I was talking to my wife and Kathy said, ‘Just walk through it and see what happens.’”

Jose still runs a flight simulator at the United Airlines Training Center, and periodically flies all over the world to stay current himself. He also works full-time as associate director of JAMLAC, an outreach of Mile High Ministries that operates out of the bottom floor of Joshua Station, an old turquoise hotel-turned-transitional housing facility for the homeless off 8th Avenue and Interstate-25.

Jose is a 1988 graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy and a former S-3 Viking pilot with more than 100 night landings on the U.S.S. Ranger and U.S.S. Constellation aircraft carriers. He served in the Persian Gulf, helped establish the no-fly zone over Iraq, and his carrier was the first “on station” in Somalia in 1992. Jose made his first carrier landing on the U.S.S. Lexington off Key West, Fla. “They fly you out in formation, four of you. I had never stepped foot on a carrier in my life. You’re flying overhead by yourself, and you circle overhead until they say it’s time to come down. I remember looking down and saying, “They’re really going to make us do this. I was trying not to hyperventilate. We were in loose formation and I was like, ‘Holy crap. Holy crap. Holy crap.’ There were 45 seconds between landings. They told us, ‘You better look good when you come in.’ You’re in super steady, tight formation and you’re so zoned in…You break off at 300 miles per hour.” After he safely completed his first touch-and-go Jose says, “I just started screaming, ‘I did it! I’m alive!’

Of course, Jose negotiates his dual professions with help from Kathy, who serves as a co-pastor of The Refuge faith community, and his JAMLAC boss, Steve, who happens to be the brother-in-law of one of The Refuge’s other co-pastors. “Usually [legal] hearings get scheduled a few months out, so I can ask for those days off. When I do have a conflict, Steve [covers] for me.”

Setting out fleeces

Jose first awakened to the need for legal aid before Kathy co-founded The Refuge, when he started a men’s group at their local church to help clients move their things into and out of nearby domestic violence shelters.

“It was all grunt work but I started talking to some of the victims,” Jose says. “They were just normal people, but the things that came up were they wanted a divorce but didn’t know how to go about it, or if they had a job, they barely made more than minimum [wage] and couldn’t get legal representation, or they wanted custody of their child, but…didn’t know what to do.”

“You really start questioning,” Jose says. “Why is this coming at me from all directions? I was happy, I was volunteering and I didn’t need anything more. I didn’t have any plan for [becoming a lawyer]. It was more, take a step and see what happens.”

“I figured, I’ll take the LSAT. If I fail, I’ll keep being dumb happy me. I was going to take a [LSAT] prep class, but it was too expensive, so I just bought a book at Barnes & Noble. I took the test, and lo and behold, I did really well.”

“Then I don’t even know if I’m going to get into law school. So I applied to DU…I couldn’t apply to CU [the University of Colorado], because they don’t allow you to work your first year. I got in. Then Kathy and I were like, ‘How are we going to pay for this?’ So I was just scanning the [DU law school] website when I saw the scholarship for people with a desire to go into public interest law.”

Classroom to courtroom

“It was crazy hard, challenging,” Jose recalls. “The time was really the hard part, the reading and homework. After one semester it was so hard, I had one month off for Christmas, and I remember telling Kathy, ‘I don’t think I’m going back. I like my life without complicating it.’ She said, ‘You’d be an idiot not to go back, to basically throw away $100,000. You’d be hard-pressed to get [the scholarship] again.’ So I went back and finished.”

“I had to volunteer 10 hours a week while I was at school,” Jose says. “But the thing that I remember that I got the most out of [law school] was the diversity of views of people. I really got to see another side of the life of the poor and how hard it is for them. The things that they deal with are things I take for granted every day. And maybe not necessarily ‘poor’ people…but ‘the underrepresented’ might be a better term.”

“If you read some [U.S.] Supreme Court opinions, they just pull stuff from thin air because it fits [their argument], but as I read through the cases I got this feeling that I don’t really like this, this doesn’t make sense to me…So I wrote a 40-50 page paper about the inconsistencies of the Supreme Court decisions regarding underrepresented people.”

During his second year in law school, Jose accepted Steve Thompson’s offer to intern at JAMLAC. After he graduated in 2008, and thanks to applying for and winning a two-year federal grant, Jose became JAMLAC’s second full-time attorney. On its $200,000 annual budget, the clinic now manages its operating expenses and pays five salaries to three attorneys, one paralegal, and one legal advocate, who can help clients negotiate the legal process in the many cases that don’t require a lawyer’s attention. JAMLAC provides free or low-cost legal assistance to more than 500 clients each year.

In the cockpit at JAMLAC

As for Jose, he typically has about 40 active civil cases going at the same time, from domestic violence cases to divorce to custody disputes.

“Normally it’s pretty straightforward,” Jose says. “You go against another attorney. In civil court hearings there’s a trial without a jury. The judge is the jury. Usually [estranged husbands and former boyfriends] just bury themselves…I’m surprised how no one is afraid to lie on the [witness] stand.”

When he’s not at a district court hearing, meeting with current or prospective clients, or doing research for his cases, Jose tries to broaden the clinic’s reach. In his two years at JAMLAC, Jose has helped expand the clinic’s referral network to local churches, domestic violence shelters, police departments, police victim advocates, and non-profits like Servicios de la Raza in West Denver. Jose also helps oversee a dozen or so “volunteer” attorneys who take on simple cases and otherwise offer JAMLAC clients legal advice.

JAMLAC recently applied for funding for a one-day-per-week satellite clinic in North Denver, because it can take some of JAMLAC’s vehicle-less clients two hours and three public buses to make it to a meeting with their attorney.

The need for legal aid

With its network of 15 statewide offices, Colorado Legal Services (CLS) is the main source of free and low-cost legal representation for low-income families in Colorado. In 2009, CLS provided legal assistance to more than 9,300 people, but according to the Legal Aid Foundation of Colorado, which raises funds for CLS, at least that same number of people were turned away because CLS did not have the resources to serve them.

Currently, there is one CLS lawyer for every 13,000 income-eligible clients in Colorado, compared to one active lawyer for every 250 people in the state.

“We really try to not duplicate what [CLS] does, since the need is so great. We’ve found that our little niche is the Spanish-speaking population,” says Jose, who is the son of immigrants from El Salvador.

About three of every four JAMLAC clients are Spanish-speakers, but regardless of what language they speak, all of them need help navigating the legal process.

“When a poor person gets in a hole, it’s so deep that we can’t understand it. Most people are going to look at someone like [Maria] and say, ‘Go get a job.’ She was a single parent. Two kids. [With her legal problems] she just can’t do it…And you know what? When you help someone like that, you’re hooked on helping people.”

*Maria is a pseudonym used to protect client confidentiality.

For more information about JAMLAC, click HERE. If you’re an attorney interested in volunteering at JAMLAC, or if you’re interested in becoming a legal advocate contact Jose directly.