Ideally, a human life should be a constant pilgrimage of discovery. The most exciting discoveries happen at the frontiers. When you come to know something new, you come closer to yourself and to the world. Discovery enlarges and refines your sensibility. When you discover something, you transfigure some of the forsakenness of the world.

John O’Donohue, Eternal Echoes: Celtic Reflections on Our Yearning to Belong

I’ve always loved history, but I started visiting historical sites —

including the Auschwitz Concentration Camp in Poland — when I was in college.

Later, while serving as a campus minister, I made pilgrimage:

- On El Camino de Santiago (The Way of St. James) in Northern Spain,

- To Gettysburg, Pa., site of the famous 1863 U.S. Civil War battle,

- To Lindisfarne, also known as Holy Island, off the northeast coast of England, and,

- To the border between El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juarez, Mexico.

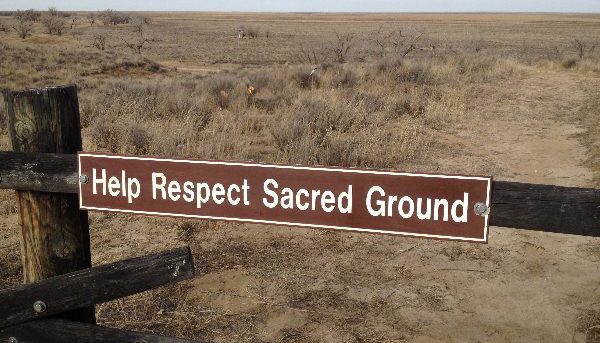

I’ve since visited Ludlow, Colo., near Trinidad, where militia killed two dozen miners and their family members during a 1914 strike. I’ve journeyed with friends to the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation and the site of the Wounded Knee Massacre in South Dakota. I’ll never forget my daytrip to the Eastern Colorado site of the Granada Relocation Center, also known as Amache, a WWII concentration camp for Japanese Americans.

In 2015, I made pilgrimage to the Holy Land of Israel and Palestine, and among other seminal experiences, I waded in the Sea of Galilee and walked the Via Dolorosa in Jerusalem.

I love to travel, but making pilgrimage is more than a hobby to me. It’s part of who I am and what I do as a minister of community engagement. The whole experience — the preparation for a trip, the journey to a site, the time I spend there and the journey home — helps me to remember. Whether what happened in a particular place is amazing and hopeful or shocking and terrible or all of the above, it’s important to me, crucial even, to remember, to acknowledge and to memorialize the past. Why? So I can live contextually (and well) in the present, and work toward a better future for myself, my family and my neighbors.

Celtic spirituality often speaks of “thin places,” where the boundary between the world as we know it and the “otherworld” is more or less transparent. Historian Mircea Eliade spoke of experiences of thin places as “hierophanies,” or manifestations of the sacred. Put another way, we make pilgrimage to encounter our Creator in a new way, because to do so in the midst of our everyday lives proves elusive. The interplay of immanence and transcendence in the act of pilgrimage frees us as much as or more than our arrival at and departure from any particular destination. We leave home to find our true home.