Last month I wrote a blog post highlighting my alma mater’s most heated sports rivalry and my part in it, and related the mindset that feeds rivalries like it to some of the violent conflicts occurring right now around the world. It might have been more appropriate to save that discussion for now since college basketball’s “March Madness” has already unofficially begun, but I wasn’t thinking that far ahead. (Incidentally, my wife likes to say this time of year is called “March Madness,” because it drives everyone around fans like me crazy.)

Anyway, for this brief blog post I’ve chosen as a starting point the work of Walter Kaufmann who translated the classic I and Thou by Jewish philosopher Martin Buber. Buber wrote about the difference between individuals and societies who perpetuate an “us” versus “them” mentality in their relationship to others, and those who follow the more humanizing and God-honoring “I-You” way of relating to others. In his introduction to Buber’s work, Kaufmann provided an incisive summary statement of the Us-versus-Them mentality.

“Every social problem can be analyzed without much study: all one has to look for are the sheep and the goats.” (Walter Kaufmann, from I and You: A Prologue to Buber’s I and Thou)

Choose a social issue, whether racism, homelessness, the growing divide between the economically rich and the economically poor, people in the midst of armed conflict, intra- and inter-religious sniping, you name it, and it is illuminated by Kaufmann’s sweeping appropriation of the biblical parable of the sheep and the goats.

The more I learn about today’s social problems, including ones in my own community, the more I agree with Kaufmann. The story of need begins and ends with the sheep and the goats. The sheep are the chosen, the blessed, the ones who are “in,” and the goats are the rejected, the cursed, the ones who are “out.”

“There is room for anger and contempt and boundless hope; for the sheep are bound to triumph.

Should a goat have the presumption to address a sheep, the sheep often do not hear it, and they never hear it as another I. For the goat is one of Them, not one of Us.

Righteousness, intelligence, integrity, humanity, and victory are prerogatives of Us, while wickedness, stupidity, hypocrisy, brutality, and ultimate defeat belong to Them.” (Kaufmann, ibid.)

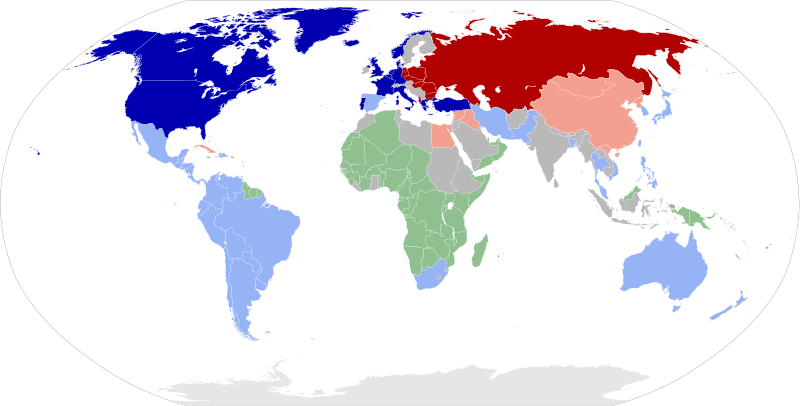

I’m not an expert on socialization, but it seems to me that most of us are raised to view ourselves as part of a “special” nation, group, tribe, class or religion. Often, by extension that means distinguishing ourselves from others who are different than us. For those of us who grew up when the Cold War was still “cold,” there were the good guys, meaning the United States and its allies, and the bad guys, meaning the Soviet Union and the communist bloc. Our identification with “the free world” was reinforced through our language, history and media. I for one spent hours reading and re-reading the techno-thriller novels of Tom Clancy, which were set amidst the machinations of the Cold War. Before Jack Bauer of 24 fame, there was Clancy’s Jack Ryan, the unassuming hero who always managed to save “us” from destruction at the hands of the communists.

With my love for Clancy’s books and my overly developed sense of patriotism, one of my favorite past-times became reviewing and tallying the U.S.’s win-loss-tie record in wars. In a similar vein, I remember my high school history teacher, a former Marine who fought in Korea, explaining the foreign policy approach of the United States under Teddy Roosevelt. He said something to the effect of: If another country challenged the U.S., Teddy would send the navy over there, and if they decided to still “flip us the bird,” the navy would shoot their finger off. I’m ashamed to say that for years I adopted that view as my own.

Faith provided another significant link in my early identity, yet looking back it’s painfully obvious to me that each successive parish or congregation to which I gave my allegiance (I was a repeated casualty of my family’s religious schisms) fancied itself the “one true Church.” Each one routinely looked down its nose at people from other denominations with pity, if not downright suspicion. And that was how we saw other Christians!

I’m thankful in hindsight to have been attending public school during the now-defunct mandatory busing era in Denver, Colo., because it brought me into regular contact with people who were different from me. For five of my 12 years in public school, I rode a bus from near my family’s house in Southeast Denver to a school on the other side of town. Three of those years were at an elementary school near Mile High Stadium, a heavily Hispanic area, and two of them were to a middle school in Five Points, a heavily African-American area.

I wish I could say those five years of experience taught me to value other cultures and particularly people from other cultures, but that wasn’t always true. In fact, I remember several noisy confrontations in middle school with two girls on our bus who were recent immigrants from Iran. Like me, most of the bus ended up shouting “U-S-A!” while the tearful girls chanted the name of Iran’s supreme religious leader “Khomeini! Khomeini!”

“True community does not come into being because people have feelings for each other (though that is required, too), but rather on two accounts: all of them have to stand in a living, reciprocal relationship to a single living center, and they have to stand in a living, reciprocal relationship to one another.” (Martin Buber, I and Thou)