In her recent New York Times article, Anne Barnard reported the comments of a doctor helping wounded Syrian “rebels and civilians” who had been attacked by their own government. When asked if he worried “that young Sunnis would take revenge on Alawites,” the doctor answered, “No…our religion teaches us to forgive.” Then, a man standing next to the doctor responded, “Should we forgive until there are no Sunni’s left alive?”

Are there limits to forgiveness? Shall we set boundaries to govern when, how and to whom we offer forgiveness? Can forgiveness be offered in concert with armed resistance and military intervention? I wrestle with these questions as much as any questions I have faced in my adult life.

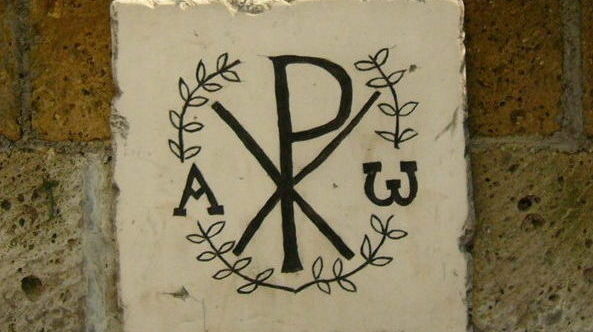

As a western Christian, I am in the midst of Holy Week with all of its remembrances of the death and resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth. I have spent the last 40 days preparing to make the spiritual journey toward the celebration of this central Christian mystery, namely, the death of God. The…death…of…God—what a bizarre concept! A God who has revealed himself as pure self-offering love has arrested me and like some kind of alien force, taken captive my thoughts, imagination and desires. I have drawn deeply from the well of this mystery and have found that it offers guidance and power and wisdom for my life, and I even think that it has something to say to the questions posed by the two Syrians struggling with the nature and limits of forgiveness. In fact, I think that this is one of the central meanings of resurrection.

As human beings, we have all at some point felt the liberation and reconciliatory power of forgiveness, the moment of release, when bitterness and anger evaporate. In that moment, we’re given strength to let go and embrace the hope and ability to redefine a once broken relationship—what Christians call “new life.”

The question I want to ask is: Where does this hope come from? Where does the “strength” to “let go” originate? And again, I have found the Christian answer to that question to be quite compelling—from beyond the grave, from the other side of death. That is precisely what seems to be happening in the moment when we are enabled to forgive. It is like the future, a hopeful future, breaks into the present and reorders our imagination and our emotions and frees us from the “death” of anger and revenge and hatred. We are liberated because something, or Someone, from the other side of this death is empowering us, enabling us to hope, to abandon our need for control and retribution. As I understand it, this is the power of the resurrection bearing its “first fruits” in this life. We are enabled to envision a better world and we are filled with hope and are thereby able to give ourselves in love to “the Other,” whoever that “Other” may be, friend or enemy.

The question, “Should we forgive until there are no Sunni’s left alive?” doesn’t lose its force or power simply by someone “believing” in the resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth. I don’t pretend to offer an easy answer to that very troubling and profound question. But I do think there is something buried, hidden, in this luminous Christian mystery and that there we can find the resources to change the way we view the future and thus how we live our lives now.

There is a line from the 2003 movie The Matrix Revolutions that I continue to find helpful. Morpheus, one of the main characters in the Matrix trilogy and one of the leaders of the resistance against the machines enslaving humanity, is driven by an almost fanatical belief in a prophecy given to him by another character, the Oracle. This prophecy—that Morpheus would find “the One” who would deliver humanity even as it is besieged in its main fortress of Zion—drives his every decision. Few share his zeal and commitment. In one telling scene, the commander of Zion’s defense forces exclaims, “Damn it Morpheus, not everyone believes what you believe!” And in a moment of great conviction Morpheus responds, “My beliefs do not require them to.”

This scene has caused me to ask a question regarding the power of vicarious faith. Can one’s faith bring benefit to others who may not share the same set of beliefs? I have come to believe, along with Morpheus, that it can. There is no doubt that many have a difficult time believing that a first-century Jewish rabbi actually passed through death and came out the other side, alive, never to die again. There are others that don’t simply struggle with the belief, but forthrightly deny it.

Regardless of whether our beliefs are weak, strong, indifferent or non-existent, I celebrate that there is a God whose death and resurrection testify to and echo a universal declaration, “Father, forgive them. For they know not what they do.”

Chris Bollegar is a priest and serves as the site pastor for Epiphany Anglican Fellowship in Broomfield, Colo. His many and varied interests include theology, hermeneutics, service for people in need and beer. He firmly supports the claim of Benjamin Franklin that “beer is proof that God loves us.”