This commentary was originally published on June 20 by Heath Haussamen of NMPolitics.net. It’s original headline: “Behind border and immigration debates are real people.”

My recent visit to a community cut in half by the U.S.-Mexico border served as a reminder that, despite our efforts at border ‘security,’ we’re still connected – and that, when we debate immigration and border issues, we’re talking about real people.

A couple of miles past the Sunland Park Racetrack and Casino, the road dead ends in a dusty place called Anapra.

A metal fence cuts through the community to mark the line between the United States and Mexico. Pull up to the fence and you see a neighborhood on the other side, in Mexico. Over there, the roads are unpaved and the homes probably don’t meet any government codes in the United States. Some might call it a shantytown.

I visited the fence in Anapra two Saturdays ago. I’ve been writing so much about Sunland Park lately that I decided I needed to spend more time in the area. I’ve made many trips to El Paso over the years but not often pulled off Interstate 10 at the Sunland Park exit and headed into the scandal-plagued New Mexico city.

The contrasts in Sunland Park are apparent. The casino is a massive structure with a gold-colored, domed roof at the entrance. During races, horses circle a man-made lake.

In the surrounding city of Sunland Park, according to the Census, 47 percent of the 14,000 residents live below the poverty line. [Editor’s note: See here for information on how to access U.S. census data.] The lack of businesses – most are across the state line in Texas – helps explain why.

The poverty is most apparent as you head west toward Anapra and the fence. The little government infrastructure that’s there – a lone fire hydrant sticks out of the ground on the side of the road – almost feels out of place among the desert brush and few homes that dot the landscape.

A cross-border conversation

At some point in history, far-off governments drew an international boundary line in the middle of Anapra. The desire to build a border crossing has been at the center of the corruption in Sunland Park (there’s lots of money at stake during consideration of a new route between the United States and Mexico). Such a crossing would open the area to commerce and reconnect the communities. I expect the desired location is where Anapra Road dead-ends into the fence. Check it out here.

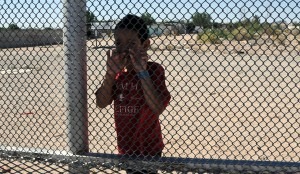

At the end of that road, on the line between two countries – a place where you can taste dust in the air – I met 9-year-old Luis, who came to the fence from his nearby home to talk with me and a friend who was with me. We quickly learned his name and age. Neither of us speaks Spanish well, and I fumbled out “Cuantos años en la escuela?” – which isn’t grammatically correct – in trying to ask him what grade he was in.

He counted out five fingers and told us, “Cinco.” Fifth grade? Fourth plus kindergarten?

Such questions went unanswered partly because of the language barrier and partly because I started wondering how safe it was to stand for long periods of time in an area where I was separated from one of the most dangerous cities in the world by only a fence.

I hated thinking that way. But I did. It’s been years since I’ve been in Cuidad Juárez because of the violence.

Luis asked if we had any money. I pulled a dollar from my wallet. I had to roll it up to fit it through a hole in the fence, and I looked uneasily over my shoulder at the Border Patrol vehicle in the distance as I passed it to him.

“Gracias,” Luis said as he took it.

My friend saw a woman in the distance and asked in Spanish if she was Luis’ mother. He said she was. Soon after that, he was gone.

Still connected

I watched Luis walk back to his neighborhood and stop to talk with someone driving an old sedan, and I wondered about his life. What’s it like to live in an area with so much corruption, violence and death? What did he think when he stared through the fence at America?

I was struck by the gravity of the moment. I’d just had a conversation with a boy in a foreign country and given him a dollar without ever leaving the United States. Despite all our rhetoric and efforts to “secure” the border, we’re still connected.

And yet, as open as the border may have felt at Anapra, it was even more so only a few years ago. The tall, metal fence was a recent project – the latest in a long trend toward controlling border crossing.

Several times recently I’ve heard stories about times when people waded across the river to visit friends, and tales about sections of land adjacent to the Rio Grande that were in the United States one year and Mexico the next depending on the flow of the river.

Today, the border is effectively militarized. My friend and I were rarely out of sight of a Border Patrol vehicle as we traveled the border near Sunland Park and Santa Teresa.

It’s even more apparent as you drive into El Paso. The wall is more ominous. There are more federal agents watching you.

There may be no place where the wealth disparity between the United States and Mexico is more apparent than when you’re passing the University of Texas-El Paso as you head into El Paso on I-10. On your left are dormitories and other grand structures. On your right is a tired neighborhood in Ciudad Juárez where buildings are falling apart and people aren’t safe in their own homes.

A bullet from that neighborhood struck a building across I-10 at UTEP in 2010. It was a stark reminder that the violence does spill over.

A small glimpse

That Saturday, pressed for time, we finished our journey at a small park in El Paso that’s on the border. Someone across the river was blasting Mexican music from his or her speakers; the sound of an accordion filled the air. I was struck, again, by how close we were to people living in another country.

A fence kept us from reaching the river. Beyond the barbed wire sat yet another Border Patrol vehicle. Across the river, we could see cars driving up and down streets.

I thought one more time about Luis, the boy in the red Tommy Hilfiger T-shirt who came up to the fence to talk with two Americans. Were people like him looking across at us as we watched them from El Paso?

I don’t have solutions to many of our great debates about immigration and border security, which I believe are quite complex problems. But I do know that, too often when we have those debates, we forget that we’re talking about real people. I write this column to share the small glimpse of those people I got that Saturday.