Parking meters in at least one major U.S. city were free today in honor of Martin Luther King, Jr., Day., a holiday observed in all 50 of the United States since 2000. Because of today’s holiday, government offices were closed. Public libraries, which contain shelves of books devoted to King and the movement he helped lead, were closed, too.

The man whose oratory and activism helped change the landscape of American society and thereby inspired today’s memorials died from an assassin’s bullet on April 4, 1968, in Memphis, Tenn., where he had been championing the cause of striking African-American sanitation workers.

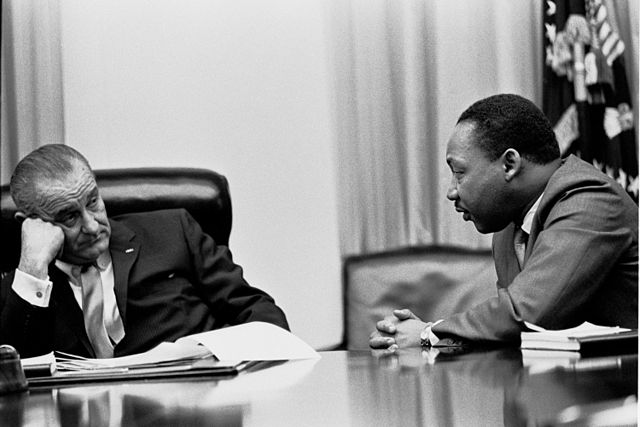

Although in life he advocated creative non-violent protest, his death sparked riots in more than 100 American cities. (Further violence was prevented by the pleas of his associates in the civil rights movement and the short speech made by Sen. Robert Kennedy of New York. King’s wife, Coretta Scott King, and their children also joined a peaceful march alongside Memphis sanitation workers, who ended their strike after they reached a settlement with city officials on April 12, 1968.) Pres. Lyndon B. Johnson declared a national day of mourning in King’s honor, and about 300,000 people attended his funeral.

The civil rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s had no shortage of leaders and activists, including A. Philip Randolph, Medgar Evers, Bob Dylan, James Meredith, Ella Baker, Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, Fannie Lou Hamer, Dorothy Height and many more. But King, a Baptist minister, came to embody the movement and give voice to it, receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964.

King grew up in Atlanta, Ga., the son of a preacher. In his autobiography, he wrote about what it was like to grow up as a negro in the American South, where encounters with the police inspired feelings of fear rather than safety, where movies arrived at the colored theatre two years after coming out, and where for a time there was no public swimming pool for negroes. He also described his thoughts on riding segregated public buses to high school, “…one of these days I’m gonna put my body up there (in the front of the bus) where my mind is.”

He entered Morehouse College in 1944 at the age of 15 and encountered the philosophy of non-violent resistance for the first time through Henry David Thoreau’s essay, “Civil Disobedience.” Later, at Crozer Seminary in Chester, Pa., he studied the work of Walter Rauschenbusch. King wrote, “It has been my conviction ever since reading Rauschenbusch that any religion that professes concern for the souls of men and is not equally concerned about the slums that damned them, the economic conditions that strangled them and the social conditions that crippled them is a spiritually moribund religion only waiting for the day to be buried. It has well been said a religion that ends with the individual, ends.” He discovered a key method of social reform when he began to study Mahatma Gandhi’s movement of non-violent resistance in India, writing that Gandhi had lifted “the love ethic of Jesus above mere interaction between individuals to a powerful and effective social force on a large scale.”

King married Coretta Scott in 1953. The following year, while King worked on his doctoral thesis from Boston University, they moved to Montgomery, Ala., where he took over the pastorate at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church located near the Alabama state capitol.

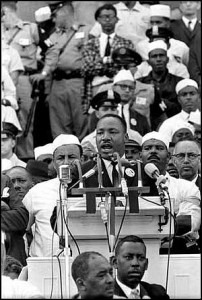

In 1955, the arrest of Rosa Parks for failing to give up her bus seat to a white passenger prompted a citywide outcry by the African-American community. Local black leaders formed the Montgomery Improvement Association to help guide the resulting boycott of the city bus system, and King was unanimously elected its president, in part since he was new to the community. With 20 minutes to prepare, he gave a speech at the association’s first mass meeting on Dec. 5, 1955.

Noted for his eloquence, he was in the public eye from that point on. Like many others, King endured arrest, abuse and death threats for his efforts to end desegregation, register African-American voters and achieve equal rights in practice for all Americans. His house was also firebombed, and as he recalled in his final public speech, he survived an early assassination attempt at a book signing in New York in 1958. Yet he continued traveling around the country in support of challenges to discrimination and injustice.

During his life critics labeled him anti-American and unpatriotic for his opposition to the war in Vietnam, and since his death he has been criticized for plagiarism and infidelity. But King’s legacy remains. The U.S. Congress designated Martin Luther King, Jr., Day a national day of service in 1994. Among the many events over the last few days in King’s honor: wreath-laying ceremonies at his Washington, D.C. memorial, a rally that garnered attention because of a recent controversy in Greeley, Colo., the King Day at the Dome rally in Columbia, S.C., and the Let Freedom Ring Celebration presented by Georgetown University and the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, which will be attended tonight by President Barack Obama.