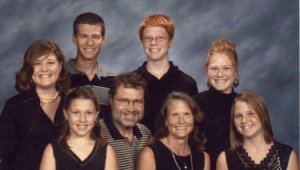

Joe and Mame Starke met in college. Joe was in his second year of medical school at Oral Roberts University and Mame was on the way to earning her master’s degree in biochemistry. Twenty-five years of marriage, 14-plus moves, and six children later, they left Joe’s thriving surgical practice in Columbia, Missouri, to learn French and serve a five-year term at a mission hospital in Galmi, Niger, in Western Africa.

“One of our mantras,” Mame says, “has been doing the next right thing. Whether…across the world, across town, across the street, or maybe…just across the room.”

Clearly, the Starkes are no strangers to upheaval. After completing Joe’s surgical internship in South Dakota, residency in Illinois, a fellowship in surgical oncology in New York, and practicing surgery in Oklahoma, the Starkes worked at a medical mission in Ghana that had been founded by one of Joe’s medical school classmates. Their youngest child, Cora, was born there, while they lived among the Ga and Akan people, in the fishing village of Teshie-Nungua outside the Ghanian capital, Accra. The Starkes even had a pet monkey, Nancy. (That might sound cool, Mame says, but Nancy was so territorial she didn’t make a very good pet.)

“We ended up spending two-and-a-half years there, loving the people and the place…It just gets in your blood,” Mame (pronounced “mAm” with a long “a”) says, noting that they always felt they would return to Africa one day.

This time they’re moving to Niger, a country with one physician for every 30,000 people. (There is one physician for about every 330 people in the United States.)

Parlez-vous français?

While Ghana and Niger are both technically in West Africa, the two countries have different primary languages. Since Great Britain colonized Ghana, the Starkes were able to speak English there, but Niger (pronounced “ni-gair” with a “g” like in the word “beige”) was colonized in the late 1800s and early 1900s by France. That’s why Joe and Mame, and their three youngest kids—Spencer, 16, Marette, 14, and Cora, 12—left last August for La Cedres language school in Massy, France. Their three oldest stayed behind—Moselle, a first-year med student, and Gunnar and Hannah, a junior and a sophomore in college, respectively.

“We made sure to give [the kids] plenty of time to adjust and to make sure that they are part of the decision,” Mame says, recalling the confirmation of their decision she and Joe received when she found a note on the family computer from one of the kids. “[It said] how they were so proud of their parents and knew they were doing exactly what they were supposed to.”

So for the last 10 months the Starkes have wrestled with the French language and culture, trying to “live” in French and not just study it.

“Knowing Joe the way I do, the language training is definitely the biggest stretch for him,” says Cheyn Onarecker, who has known Joe since they lived on the same dorm floor as freshmen at ORU in 1977. “It’s tough for a farm boy from Sublette, Kansas, to sound like he grew up on the streets of Paris.”

As the Starkes’ vocabulary and proficiency has grown, they’ve kept in touch with their multinational SIM (Serving in Mission) team in Galmi. (Joe has visited Galmi twice; Mame has visited once.) This month they’ll return to the U.S. for a short visit, then set off for Niger at the beginning of August.

Project Galmi

Once they arrive in Galmi, the Starkes will work with patients from the Hausa, Fulani, Tuereg and Djerma tribes. The Sahara Desert covers about 80 percent of Niger, a country about twice the size of Texas, forcing many patients to travel great distances to Galmi Hospital to receive treatment. In Niger, as elsewhere in Africa, family members often help nurse the patients back to health, staying at the hospital to sleep by or under the patient’s bed.

While many NGOs, particularly faith-based groups, have moved from running mission hospitals to operating medical clinics and providing disaster relief, there’s no getting around the need for a hospital with an operating room in order to do surgical procedures. In fact, one of Joe’s goals for their time in Niger is to set up a surgical residency training program for Nigeriens and West Africans at Galmi Hospital. Galmi itself was founded by SIM in the early 1950s, and currently has about 160 Nigeriens and 10 expatriate staff, including 20-25 staff with families. The hospital also has a working HIV/AIDS clinic.

According to Galmi Hospital’s website, more than 100,000 patients annually come to Galmi for help with life-threatening or debilitating illnesses.

“The people of Niger live on the brink of famine,” Mame says. “If rains come and the harvest is good, they survive, but if the rains do not come and the harvest is poor there will be hunger. If the harvest is very poor some people will starve.”

Despite isolated cases of kidnappings of foreign nationals and tourists, and, as the U.S. State Department puts it, “conditions of insecurity” in northern and western Niger, the Starkes aren’t concerned for their safety. Instead, they plan to focus on establishing a good rhythm to their days, beginning with devotions, breakfast and coffee at 5 a.m. Joe felt called to be a doctor when he was 17, but he decided to become a surgeon because he likes to work with his hands and take time to get to know his patients, which is what he will get to do when he heads to the hospital for rounds and surgery around 7 a.m. each day. He’ll return home for a “siesta” from noon to 1:30 p.m., then return to the hospital for more rounds and surgery until about 6 p.m. Mame and the kids will at least initially focus on homeschooling and connecting with the local churches in Galmi, taking advantage of spotty internet access to stay connected with friends and family back home, and experimenting with the local cuisine. They also plan to learn Hausa, the main tribal dialect spoken in Niger, to help them get to know their neighbors and the Nigerien staff at the hospital.

A new kind of medical practice

When Joe’s medical practice threw a going away party for the Starkes last summer, about 200 of Joe’s colleagues and their spouses got to hear Joe and Mame share about the work in Niger. Many of them expressed an interest in taking short-term trips to Niger to offer their services, a sign that by their example the Starkes are helping to mobilize a key community of people to serve those in need in Niger.

“Health professionals are a compassionate group or they would not be doing what they are doing,” Mame says.

Joe’s college friend Cheyn thinks “compassionate” especially applies to the Starkes, recalling a time in medical school when Joe helped him pay off his tuition so he could continue his studies.

“[Joe and Mame] were both raised in rural America. I think that background is one of the keys to their ability to set aside the…lifestyle of the typical American…They always challenge me and my family not to settle.”

Visit the Starke’s website to follow their progress in Niger.